Jenny Saville

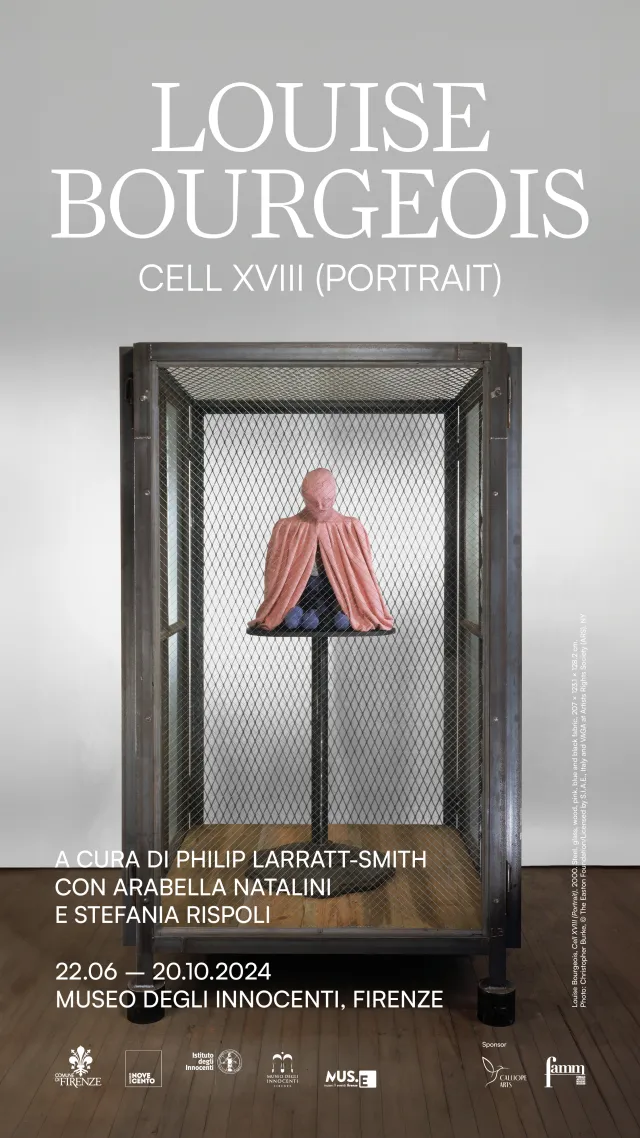

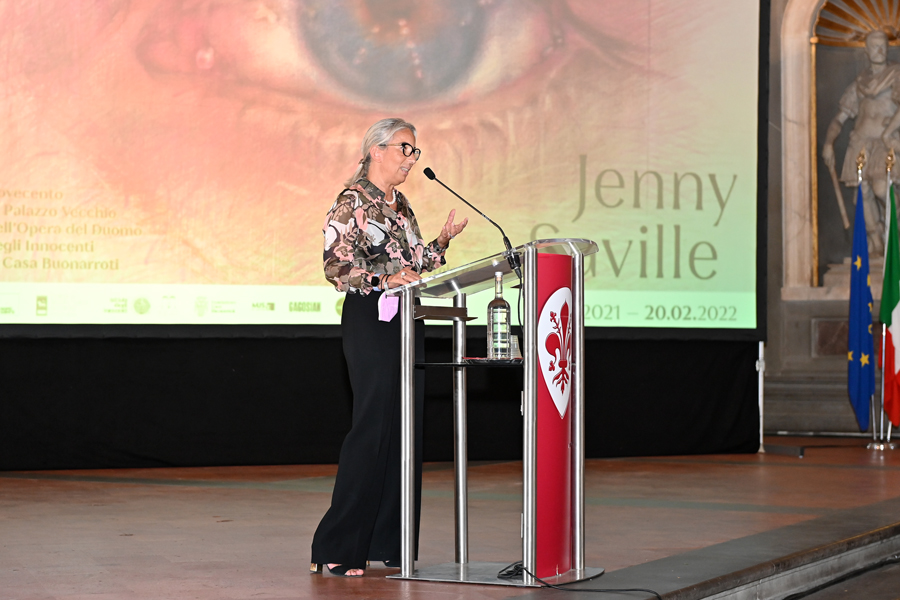

From Sept. 30, 2021 to Feb. 20, 2022, the city of Florence will welcome one of the greatest living painters and a leading voice on the international art scene, Jenny Saville, who will be the subject of an exhibition project conceived and curated by Sergio Risaliti, director of the Museo Novecento, in collaboration with some of the city's major museums: the Museo di Palazzo Vecchio, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Museo degli Innocenti and Museo di Casa Buonarroti.

The exhibition, sponsored by the City of Florence, organized by MUS.E and supported by Gagosian, is a unique encounter between the ancient and the contemporary and invites the public to discover the work of Jenny Saville (May 7, 1970, Cambridge) through a series of paintings and drawings from the 1990s and works created especially for the exhibition.

Saville transcends the boundaries between figurative and abstract, between informal and gestural, managing to transfigure the chronicle into a universal image, a contemporary humanism that puts the figure, be it a body or a face, back at the center of art history to give image to the forces that act within and against us. Like no other artist of our time she has left postmodernism behind to reconstruct a close dialogue with the great European painting tradition in constant confrontation with the modernism of Willem de Kooning and Cy Twombly and the portraiture of Pablo Picasso and Francis Bacon.

The exhibition itinerary outlines the strong correlation between Jenny Saville and the masters of the Italian Renaissance, particularly with some of Michelangelo's great masterpieces. Certain data emerge, such as the monumental scale of the paintings, a hallmark of the artist's figurative language since the early years of her career, as well as her research focused on the body, the flesh, and on female subjects who are nude, mutilated or crushed by weight and existence.

In the halls of the Museo Novecento, between the ground floor and the second floor, a conspicuous series of paintings and drawings will be on display, about a hundred medium- and large-format works covering a wide span of time, ranging from the early 2000s to these recent months. In the museum's external loggia, a

window facing the square to make visible both day and night a large-format painting displayed above the altar inside the former Spedale church, a monumental portrait of Rosetta II (2000-06), a young blind woman known to the artist and portrayed as a blind cantor or mystic in ecstatic concentration. A comparison strongly desired and sought by the museum director with Giotto's wooden Crucifix suspended in the center of the nave of Santa Maria Novella, clearly visible from outside the churchyard when the Dominican basilica's portal is open.

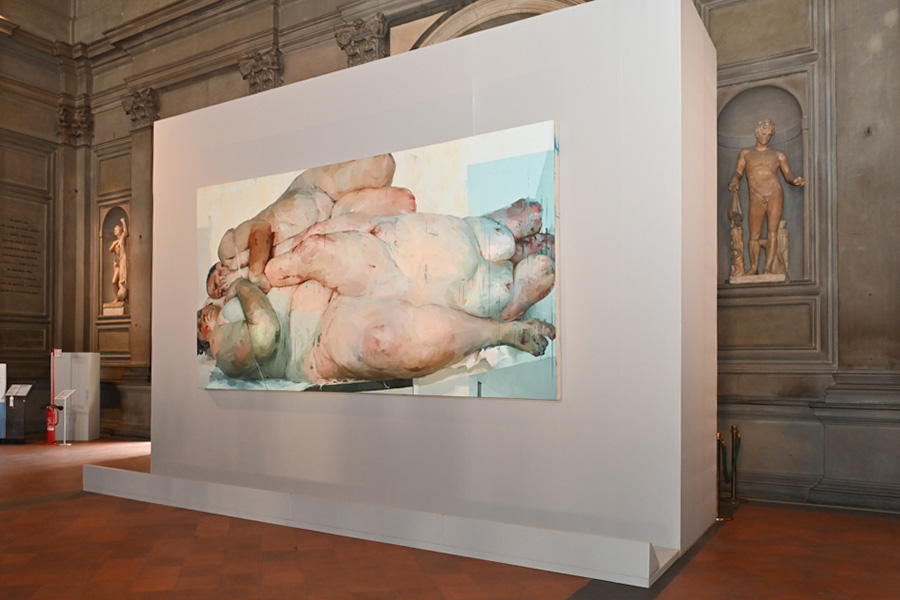

The most resonant monumental work is displayed in the Salone dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio, Fulcrum (1998-99), which definitively consecrated Jenny Saville with her first solo exhibition, Jenny Saville: Territories at the Gagosian Gallery in 1999. Saville's large painting dialectically enters into antithesis with the masterpieces assembled in the sublime setting of the Salone delle Battaglie, so named for the frescoes painted by Vasari and his school to celebrate the victories of the Florentines against their adversaries. The Salone is enriched with sculptural groups featuring the Labors of Hercules (1562-1584) by Vincenzo de' Rossi, as well as Michelangelo's Genius of Victory (1532-34), an extraordinary example of anatomical counterpoint and the unfinished. Formally, Jenny Saville's work seems to want to exhibit a comparison with the language of sculpture, given the monumental dimensions of her images and the strong plasticity of the

figures. Fulcrum 's representational space is entirely occupied by the mass of three recumbent bodies, indeed by the flesh, and the faces and individualities of the two women and the young girl, forced into an embrace with dramatic overtones, are barely distinguishable.

Saville's passionate and engaging dialogue with Michelangelo's works and iconography reaches its acme at the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo in Florence, part of the monumental complex of the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore. Here, in the room where the Pieta Bandini (c. 1547-55), among the last 'labors' of the 'divine' Buonarroti, is kept, a large-format drawing - about three meters in height - that the London-based artist began to devote himself to after a visit to Florence two years ago, will be on display. The polished and shining body of the Christ of Michelangelo's Pieta, strongly disjointed in its pose, the loving expression of Nicodemus, concealing the artist's own self-portrait and supporting the weight of the Messiah, the contained torment of the Mother, find in the Study for Pieta drawing (2021) by Saville a natural counterbalance animated by the intense gazes of the characters holding up a young boy, a victim perhaps of political or ideological barbarism, perhaps a migrant, an antagonist or martyr of terror. Avoiding the identification of space and time, drawing the figures without recognizable clothing and signs as to social, political, ethnic affiliation, here Saville declares, in a contemporary but equally universal and archetypal version, the condemnation of all human violence, making the theme of pietas, the experience of mourning and mourning speak with dramatic signs. A current, present and timeless Vesperbild of the same universal poetic tragicness as that of the sculptural group created by Buonarroti in the extreme phase of his career

art.

Similarly, the conception of the female figure in relation to motherhood is encapsulated in the two paintings presented in the Pinacoteca of the Museo degli Innocenti. Between the Madonna and Child (c. 1445-50) by Luca della Robbia and the Madonna and Child with an Angel (1465-76) an early work by Botticelli, the large painting The Mothers (2011) by Jenny Saville, with a strong evocative impact, reveals the fulminating timeless short-circuit of this theme, welcomed into a building where, since the time of Brunelleschi's project, the need for a commitment to the care of abandoned children and the promotion and protection of children's rights has been felt. A second large-scale drawing will be displayed here, Byzantium (2018), a different version of Pieta in which the graphic work accompanied by very resentful color interventions seems not to have stopped in search of the right pose, following likewise the movement of the bodies.

In the rooms of Casa Buonarroti, a place of memory and celebration of Michelangelo's genius, Jenny Saville's drawings Study for Pieta I (2021) e Mother and Child Study II (2009) present a conscious and by no means anodyne homage to Michelangelo's drawings and sketches (1517-1520). There is no shortage, however, with paintings such as Aleppo (2017-18) and Compass (2013), of themes dear to Saville's poetics, so tenaciously linked to the contemporary. Drawings of strong emotional and sign-like impact concert with one of Buonarroti's most celebrated and admired works on paper, the so-called 'cartonetto,' Mother and Child (c. 1525). Complementing this artist-to-artist dialogue are two earthen sketches, one attributed to an artist in Michelangelo's circle and the other to Vincenzo Danti, a small-scale reproduction of the Medici Madonna, as well as a pair of small Michelangelo inventions for a Transfiguration and an Etruscan cinerary urn.

Considered heir to the so-called 'London School," Saville is convinced, like Bacon, Freud or Andrews, that the potential of painting is yet to be explored by overcoming the distinction between abstract and figurative, as well as those between expressionism and informal. Always seeking truth in painting to lay bare the expressive immanence of the body, the artist works on the studio model and photography. To construct his images, so powerful and dazzling, so overwhelming and striking, he collects photographs and clippings from newspapers and catalogs, mixing art history and archaeology, scientific and news images, without creating hierarchies or distinctions between beauty and abjection, brutality and venality, tenderness and cruelty. His subjects belong to the classical tradition: faces, naked bodies, groups of several figures, reclining or standing figures, motherhood and pairs of lovers presented in poses reminiscent of Etruscan statuary or classical models from the Renaissance and modern traditions, Egyptian or archaic art.

If the young Michelangelo became the greatest sculptor of his era for creating a monumental statue, more than five meters high, the David, the champion of male beauty according to neo-Platonic culture, Jenny Saville, on the other hand, achieved fame through huge depictions of nude female bodies, portrayed posed on stools or reclining, exhibiting prococious sexual forms comparing herself on this level with other painters such as Titian and Gustave Courbet.

Exhibitions and exhibition spaces

Ticketing and reservations

You may also be interested in.

From my perspective

Impressionists in Normandy

Alphonse Mucha. The Seduction of Art Nouveau.

Steve McCurry Children

Escher

An unexpected legacy

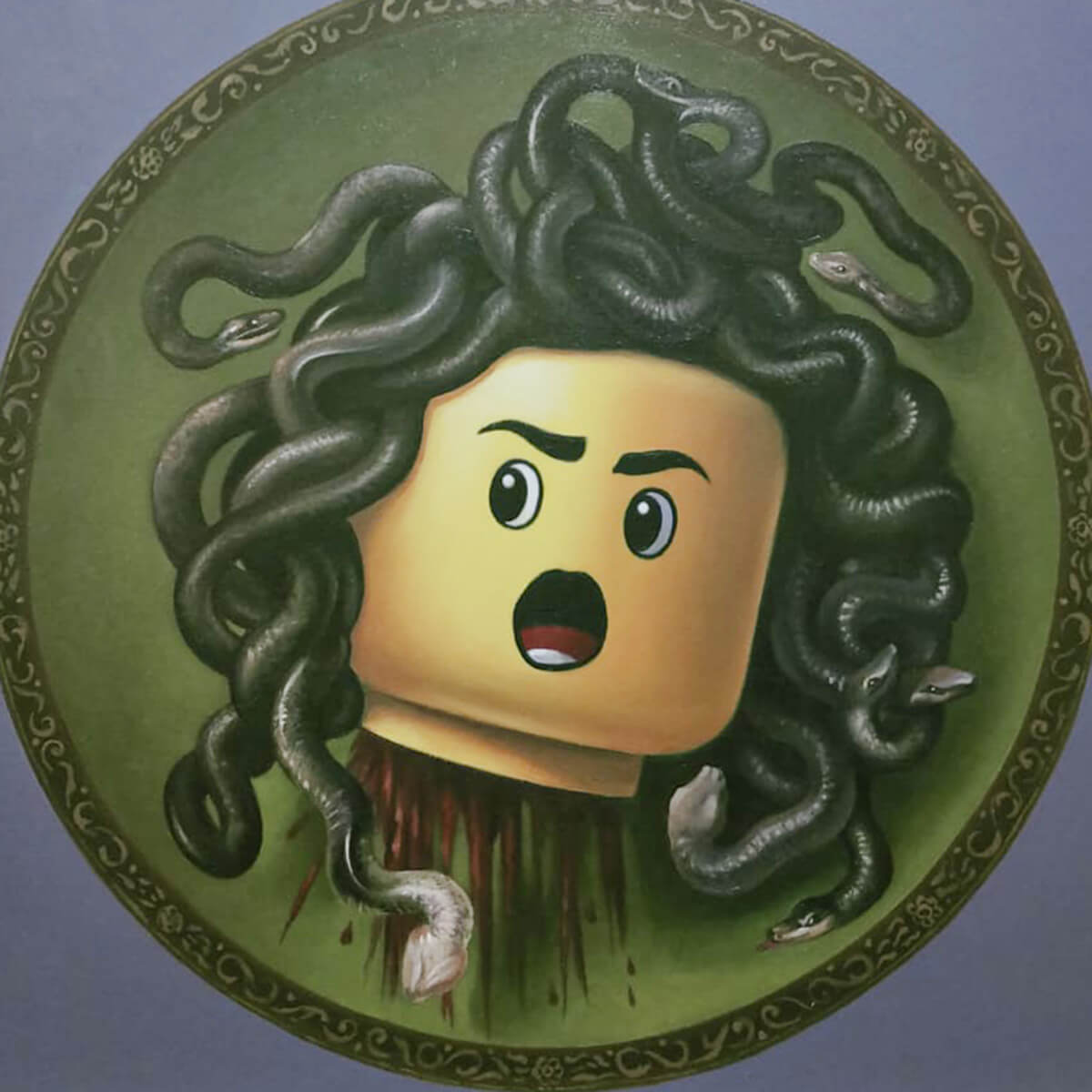

I Love Lego

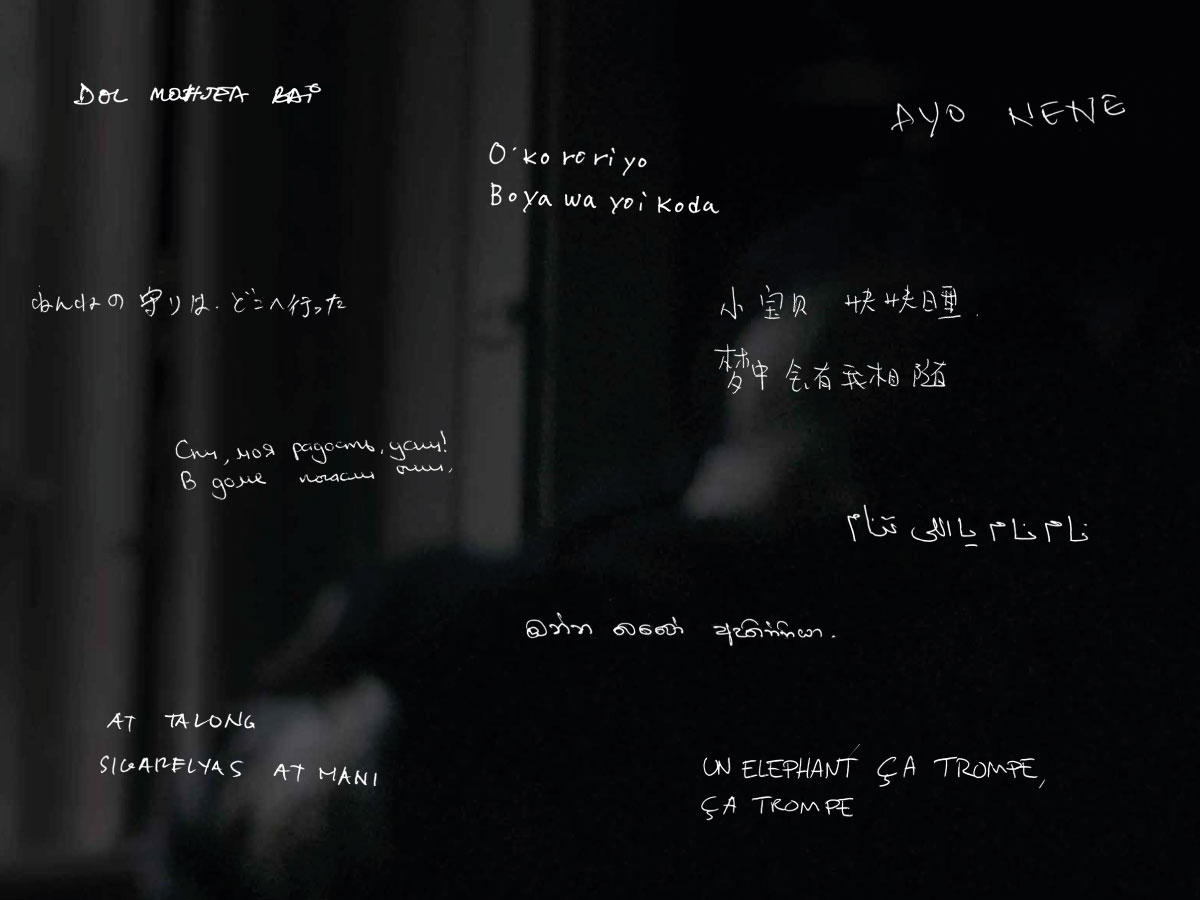

'unconnected'

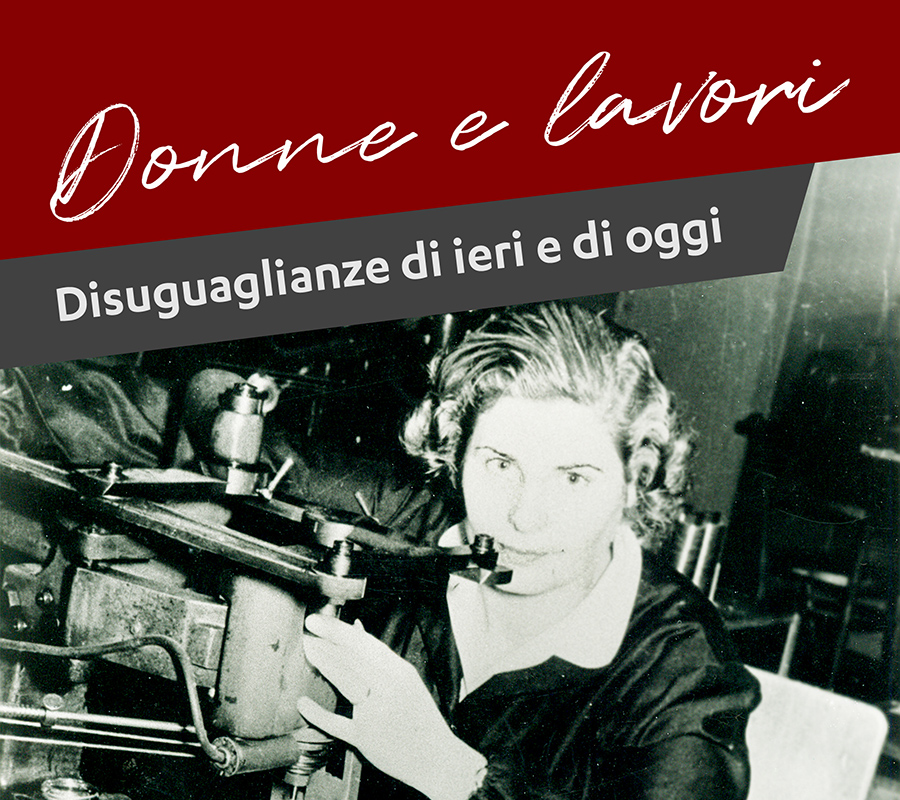

Women and jobs

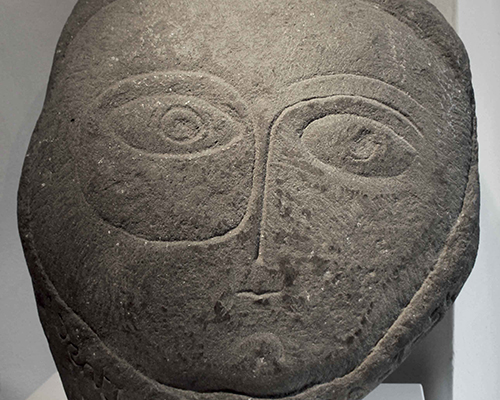

Venturino Venturi Mater

Hallelujah Tuscany

Children forever!

BONELLI STORY.

Tony Cragg, Transfer

Marina Ballo Charmet - Tatay

Y.Z. Kami, Light, Gaze, Presence

And the other half I will keep

Yokai Japanese Monsters